Running out of gas while you’re driving is a major inconvenience. It can leave you stranded, sometimes miles away from the nearest service station. It can take hours of your day to reach your destination. And depending on where your vehicle has stopped, it can put you in an unsafe situation.

Get to know and directly engage with senior McKinsey experts on EREVs

Andreas Venus is a senior partner in McKinsey’s Berlin office, Kevin Laczkowski is a senior partner in the Chicago office, Patrick Hertzke is a partner in the London office, Patrick Schaufuss is a partner in the Munich office, Philipp Kampshoff is a senior partner in the Houston office, Shivika Sahdev is a partner in the New York office, and Timo Möller is a partner in the Cologne office.

Yet more and more of today’s drivers face another potential inconvenience: running out of battery. This is what’s known as range anxiety; it encompasses the unease that can surface for the driver because of an electric vehicle’s (EV) limited driving distance (at least, compared with an internal-combustion-engine [ICE] vehicle), a lack of convenient charging stations, and the need to recharge frequently. Range anxiety, along with the price tag of the EV itself, is a major concern for consumers considering the purchase of an electric vehicle. For prospective owners who live in apartments or homes without access to overnight charging, as well as those who would take long-distance trips, the potential lack of public charging stations can be a concern. And while most drivers have a daily commute of less than 50 miles, others drive much farther to get to and from work.

EREVs—or extended-range electric vehicles—stand to quell range anxiety and may boost EV sales around the world. Read on for more on what EREV growth may mean for global momentum toward electrification.

Learn more about McKinsey’s Automotive & Assembly Practice.

What are the types of EVs, and how are EREVs different from others?

There are five distinct types of electric vehicles:

- Hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) have both an internal-combustion engine and an electric motor, which assists only at low speeds. The battery is charged either by the combustion engine or through recuperation when braking. Honda’s Accord line, for example, features an HEV model.

- Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) are powered by an electric motor as well as a small combustion engine. They have an all-electric range of 20 to 60 miles and can be charged at a regular EV charging station. Toyota’s Prius line includes a plug-in hybrid.

- Extended-range electric vehicles (EREVs) are sometimes included in the PHEV category, but there are key differences between the two. Whereas PHEVs use a parallel electric-motor and ICE powertrain configuration, EREVs typically include a small ICE-powered generator that recharges the battery pack. Both EREVs and PHEVs can be charged at EV charging stations, and their ICE engines can be refueled at traditional gas stations. But many PHEVs can only slow charge using home chargers or public chargers, whereas EREVs can use AC chargers and newer DC fast chargers. Finally, EREVs offer a longer driving range than PHEVs: usually between 100 and 200 miles, compared with 20 to 60 miles for PHEVs.

- Battery electric vehicles (BEVs) rely solely on their battery for power. They produce no tailpipe emissions, have no combustion engine, and can typically drive between 200 and 500 miles before needing to recharge. The Tesla Model 3 and the Chevy Bolt are examples of BEVs.

- Fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) use only electric motors. Their electricity is generated in fuel cells and can be stored in a small buffer battery. Fuel cell vehicles use hydrogen (which is compressed into tanks) as fuel. Toyota’s Mirai and Hyundai’s Nexo are examples of FCEVs.

Looking for direct answers to other complex questions?

What is the current market presence of EREVs?

China is the only market where EREVs are currently available at scale. The vehicle’s strong sales momentum there has caught the attention of auto manufacturers in Europe and the United States as one potential way to boost EV sales growth. EREVs, such as the now-discontinued Chevy Volt, were part of the first wave of vehicle electrification in the 2010s. But they didn’t take off, because early EV adopters were interested mainly in pure BEVs. Today, though, a wider range of Americans and Europeans are buying EVs—not only the early tech-savvy adopters but also mainstream car buyers. For automakers that have developed BEV production lines but may have struggled to get sufficient sales volume, they can often develop EREVs on the same BEV platform and achieve better economies of scale.

At present, only a few EREVs are commercially available. But in different geographies, a number of new EREVs are scheduled to hit the market in 2025:

- In the United States, soon-to-release EREVs in the SUV and truck segments include the 2025 Ram 1500 Ramcharger, which reports a 145-mile pure electric and 690-mile total driving range.

- In Canada and the United States, the Volkswagen-backed Scout Motors has announced several EREV models. According to the company, these models have received considerably more deposits than they saw for their BEVs.

- In China, Li Auto has introduced several EREVs, including its L9, which reports a 134-mile electric range and an 817-mile total range. Aito’s M9 reports up to a 170-mile electric range and a total range of up to 871 miles.

Learn more about McKinsey’s Automotive & Assembly Practice.

What are consumers’ perceptions of EREVs?

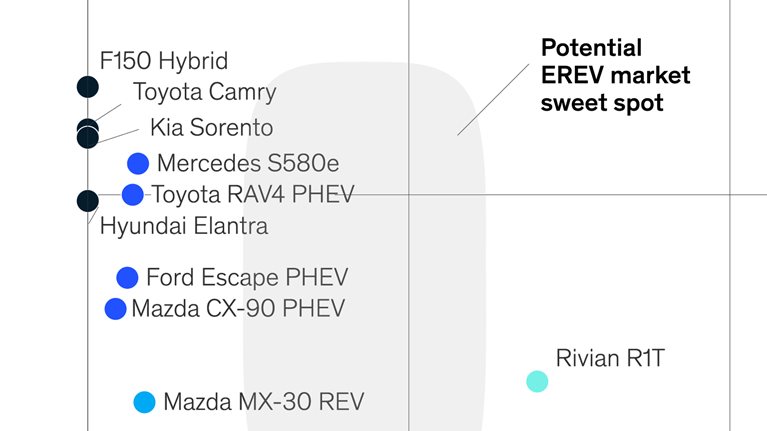

McKinsey’s late-2024 survey of more than 2,800 new-car buyers in the United States and 2,300 in Germany and the United Kingdom found that a sizable segment would consider an EREV for their next vehicle purchase if the option were available. Two-thirds of these potential buyers noted an intent to purchase an ICE or hybrid vehicle in the absence of an EREV option. This finding indicates that EREVs could motivate more ICE vehicle owners to make the transition to electric driving (exhibit).

The survey also found that interest in EREVs was higher among owners of premium-brand vehicles than among owners of mass-market-brand cars. Current owners of larger cars and SUVs also expressed slightly higher interest in EREVs, compared with owners of smaller cars.

How do regulations affect EREV adoption?

At the moment, the United States’ regulatory environment may make it the most favorable market for automobiles generally—including EREVs. There may also be significant opportunities in the European Union, despite quickly approaching deadlines; by 2035, zero-emission vehicles must account for all new-vehicle sales in the region. (Since EREVs are a type of plug-in hybrid vehicle, they don’t count as zero-emission vehicles.)

When considering where to sell their EREVs, auto manufacturers should consider the European Union’s narrow window of opportunity against potential development timelines. This can help them determine whether EU consumer demand will generate enough profit to warrant further investment in EREV powertrains.

Unlike the European Union, the United States has no zero-emission requirements in place for new-car sales (although some states have implemented their own requirements).

How could EREVs contribute to the transition to fully electric transportation?

EREVs could help smooth the transition from ICE vehicles to BEVs by serving as a bridge technology for consumers as charging technology continues to improve and BEVs become more cost-competitive around the world. Car buyers who are hesitant to buy an EV could be tempted by EREVs, provided that manufacturers can clearly articulate the benefits of the technology. Aside from clear consumer communications, manufacturers will want to minimize time to market and simplify supply chains and production.

Learn more about McKinsey’s Automotive & Assembly Practice. And check out EV-related job opportunities if you’re interested in working with McKinsey.

Pop quiz

Articles referenced:

- “New twists in the electric-vehicle transition: A consumer perspective,” April 22, 2025, Patrick Hertzke, Patrick Schaufuss, Philipp Kampshoff, and Timo Möller, with Anna-Sophie Smith and Felix Rupalla

- “Could extended-range EVs nudge more car buyers toward full electric?,” February 10, 2025, Kevin Laczkowski and Patrick Hertzke, with Anna-Sophie Smith, Deston Barger, Madhumitha Aravanan, and Paul Hackert

- “How European consumers perceive electric vehicles,” August 5, 2024, Andreas Venus, Patrick Schaufuss, and Timo Möller, with Anna-Sophie Smith, Felix Rupalla, Jan Paulitschek, and Laura Solvie

- “Exploring consumer sentiment on electric-vehicle charging,” January 9, 2024, Lauritz Fischer, Felix Rupalla, Shivika Sahdev, and Ali Tanweer